Contributor license agreements are a thing. As much as I dislike the bureaucracy of them, they do provide some additional cover to the owners of an open source project, and some companies insist on having them. I find myself in such a situation in the SciTools organisation, for which I am one of the lead developers. We have a CLA form, a signing process, and a list of signatories - but the really painful part is having to remember to cross check that list of signatories each time we want to merge a pull request.

This is the story of how (and to some extent why) I went about automating that process.

In early August 2017, I ran a 2 day tutorial for my team to improve knowledge and give practical experience of using and creating "webapps, webhooks and SaaS". I picked off a few useful technologies to play with, and presented a few hours of material to them. In particular, I focused on tornado, the GitHub API, and Heroku.

Next, we took the knowledge I presented and came up with a bunch of ideas to hack on. I decided to focus on the pesky human-in-the-loop process of cross checking our CLA signatories list, and see if I could turn it into a fully fledged CI service in less than 1.5 days (in practice, since I led the tutorial and helped others whenever they got stuck, I only got a fraction of that time actually working at my machine).

My basic plan was as follows:

- Write a CLI tool that gets our CLA signatories list and prints it

- Write a CLI tool that gets the authors of a GitHub PR (there may be more than one - it is the commits we actually care about)

- Write a CLI tool that updates a PR's status and labels based on the status of a CLA check

- Write a webapp that listens for GitHub webhooks, and applies the tool developed each time a PR is created/updated

Since I knew I was targeting a tornado webapp at the end, I ensured all of the key components were written as asynchronous coroutines, and only at the very top level of the CLI tool would I call the coroutines synchronously. It is important to note that writing coroutines generally requires making use of other coroutines - it is somewhat invasive, and much easier to start off in the knowledge that you want your code to be asynchronous.

Calling (asynchronous) coroutines from a (synchronous) CLI tool

The pattern that I followed to make my tools asynchronous, but my CLI synchronous was simply to use tornado's run_sync method on an IOLoop instance:

@tornado.gen.coroutine

def my_coroutine(arg1, arg2):

result1 = yield another_coroutine_1(arg1)

result2 = yield another_coroutine_2(arg2)

return result1, result2

def main():

...

# argparse stuff

...

# Finally, call the coroutine with the argparse arguments.

result1, result2 = tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.current().run_sync(

lambda: my_coroutine(args.arg1, args.arg2))

Using the GitHub API for labels and statuses

A big part of the challenge was making use of the GitHub API (v3) to query information about the PR in question, and to update things like the commit status and PR labels.

The first thing to note is the GitHub data model. It is a strange quirk that pull requests are actually issues (though not all issues are pull requests), and pull request statuses are actually statuses on commits. Updating the labels of a pull request therefore involves using the POST /repos/:owner/:repo/issues/:number/labels API. Updating the commit status first involves finding the HEAD commit of the pull request, and then using the POST /repos/:owner/:repo/statuses/:sha.

Authentication of GitHub API

Because I was writing this tool for a very niche set of repositories, I didn't need anything fancy in terms of authentication. I simply created a personal access token with the necessary scopes, and updated all GitHub API calls to include the extra Authorization: token ${TOKEN} http header. When it comes to deploying this, there is an option to set secure environment variables on Heroku (under settings) which is where the token is put under the environment variable name TOKEN.

If I did need a more sophisticated authentication scheme there are two options available. Both have reasonably good solutions for use with tornado:

- OAuth - useful for interactive (mostly browser based) services that act at the time the user visits the service

- GitHub apps - useful for non-interactive services, where scheduled tasks or other event triggers require authenticated work to occur (e.g. a status updater when a PR is modified)

It is worth noting that, despite my description of GitHub apps, tools like Travis-CI could happily make use of personal access tokens as a means of setting commit statuses because they are happy to report as the @travis-ci user, not the user who registered a repo's travis-ci integration.

An example of GitHub's OAuth with tornado can be found on GitHub at jkeylu/torngithub, and an example of creating a GitHub app with python can be found in a gist I created at https://gist.github.com/pelson/47c0c89a3522ed8da5cc305afc2562b0.

Writing a webhook

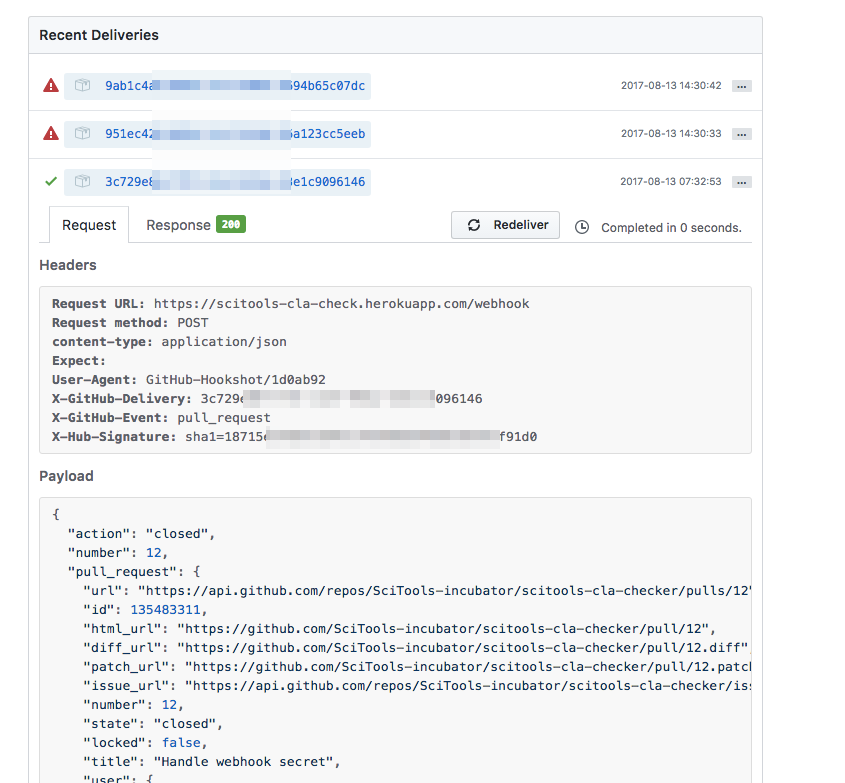

GitHub webhooks are simply a POST request to a pre-determined URL. Of course, you need to have a webapp listening at that URL in order to do anything with it. In this instance, I simply pushed my webapp up to the cloud (Heroku in this case). The docs for webhooks are pretty good, but the single most important piece of advice for when creating one is to take a look at the "manage webhooks" page. You can find this in your webhooks' settings page, and you get some invaluable info about the deliveries that have been made, as well as having a button to get the hook redelivered:

Preventing man-in-the-middle webhooks

The default webhook essentially requires a POST request of the right form sent to the right address. With this information anybody could submit their own POST request and get your service to do something. If you want to have confidence that the POST request does originate from GitHub, and hasn't been tampered with, you need to define a secret that GitHub will use to sign the POST content. The secret can be anything, and will be used to create a HMAC digest of the request being sent. You simply need to use the same secret to create a digest on the webapp side, and confirm that they match. If they don't match, the message hasn't come from GitHub.

The docs on "Securing your webhooks" are pretty extensive. They show an example in ruby, but almost exactly the same calls are required to validate the HMAC signature in Python:

import hmac

import hashlib

hmac_digest = headers.get('X-Hub-Signature', None)

webhook_secret = os.environ['WEBHOOK_SECRET'].encode()

# Compute the payload's hmac digest.

expected_hmac = hmac.new(

webhook_secret, self.request.body, hashlib.sha1).hexdigest()

expected_digest = 'sha1={}'.format(expected_hmac)

if hmac_digest != expected_digest:

logging.warning('HMAC FAIL: expected: {}; got: {};'

''.format(expected_digest, hmac_digest))

self.set_status(403)

Tornado async user agent

Towards the end of the 2 day session, we were all frantically trying to deploy our own developments, and as the leader of the tutorial it was inevitable that I would be called up to help each group finalise their work. I too was frantically trying to get my CLA checker deployed, and was running up against the most peculiar of issues...

Tornado's AsyncHttpClient was returning a 403 (Authentication failure) on the GitHub API on my Heroku deployment, but not locally. In addition, I was able to ssh onto my Heroku instance and verify that the exact same call using the exact same token worked like a charm using requests and curl.

Had I not been all over the place trying to help others out, and perhaps had a shorter iteration cycle (I was having to deploy to Heroku to debug), I may have solved the problem a little quicker. It took a good hour to realise that the problem was that I was getting 403 because the User-Agent wasn't being set by AsyncHttpClient, and GitHub have a strict enforcement policy on it needing to exist. Simply adding the user agent when calling fetch solved this issue:

yield http_client.fetch(URL, method='GET',

user_agent='MY-CLI-CHECKER',

headers=headers)

Round-up

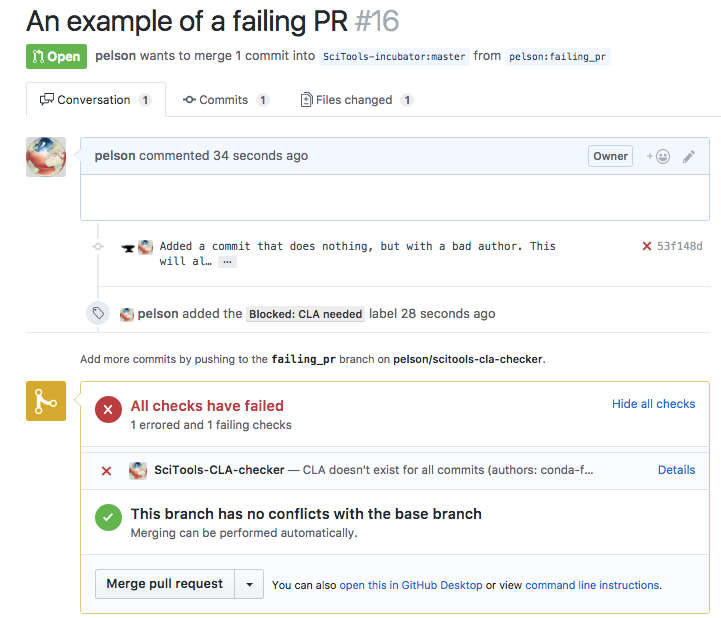

So there you have it... I put together a CLA checking service in less than a couple of days, and in the process was able to help my team learn about webapp, Heroku and the GitHub API. A screenshot of the kind of behaviour I have created shows both the status and labels being set when a CLA is missing:

Although I've actually written a CI type tool on top of the GitHub API before, there were a bunch of things I learnt along the way. Hopefully this shows you that you really can have the integrations you've always dreamed of on GitHub with just a small amount of development effort.

You can see the code for the SciTools CLA checker I produced at SciTools-incubator/scitools-cla-checker.